Scientific Horizons of Karazin: A Deep Dive into the Past of the World's Oceans from the Utyevsky Polar Researchers

Scientific research is the alpha and omega of Karazin University. Therefore, we decided to learn more about evolution, bipolar distribution of organisms, and the discovery of new species from the distinguished polar scientists who study the world's oceans from the Arctic to Antarctica, the Utyevsky brothers, Serhiy and Andriy.

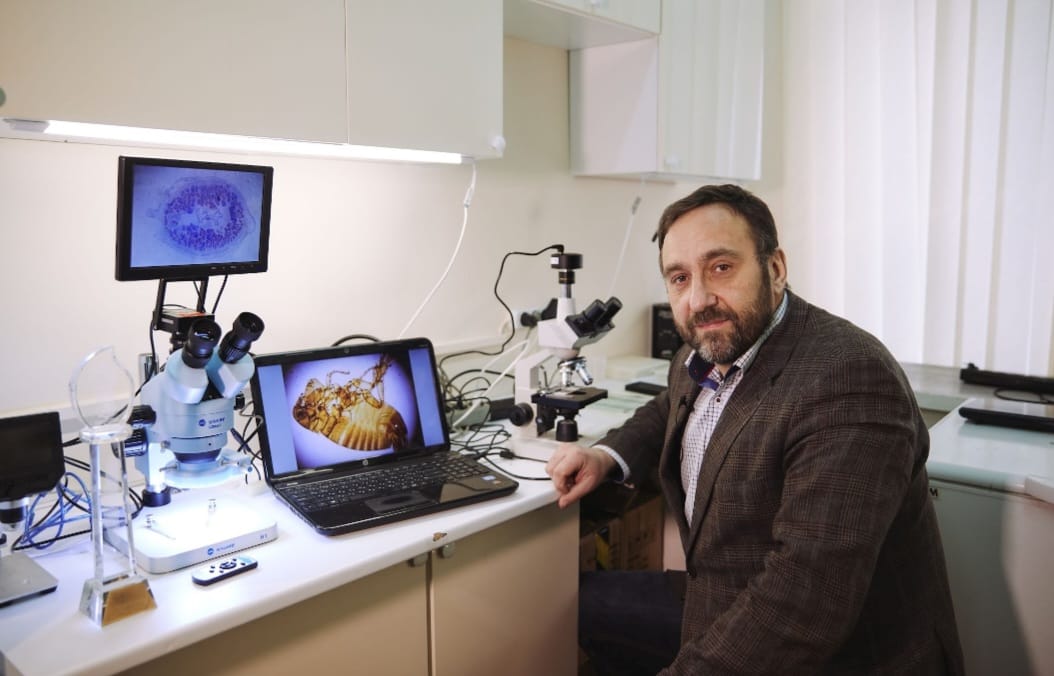

Serhiy Utyevsky is a Ukrainian zoologist specializing in leeches and holds a Doctorate in Biological Sciences.

Andriy Utyevsky is a Ukrainian zoologist specializing in leeches and is an Associate Professor at the Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology at V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University.

In this article, we will detail how Andriy and Serhiy Utyevsky discovered a new species of Antarctic leeches and established that millions of years ago, its ancestors migrated first from Antarctica to the Arctic, and then back to Antarctica. They conducted this work in collaboration with foreign colleagues Alexander Beletsky and Joanna Cichotska from Poland, Mario Santoro from Italy, and Peter Trontelj from Slovenia.

The Long Journey Back to Antarctica

Understanding past events is necessary for explaining what we observe today. The world looks like this because of its history. Modern evolutionary biology has incredible tools for studying the past, which can give us some insight into the future, as certain events tend to recur. Thus, we can expect that something that has happened before may happen again. There are problems that are difficult to explain, among them the bipolar distribution of organisms. Why do related organisms live in the high latitudes of both hemispheres but are absent in the tropics?

An international team of zoologists, including Andriy Utevsky and Serhiy Utevsky from Ukraine, Alexander Beletsky and Joanna Cichotska from Poland, Mario Santoro from Italy, and Peter Trontelj from Slovenia, studied the distribution of fish parasites — piscioline leeches. They discovered a previously unknown species living around Antarctica.

A thorough study of the external and internal structure of the new species, as well as its nuclear and mitochondrial genes, showed that the closest relatives of the Antarctic leech live in the cold waters of the northern Pacific Ocean. An unusual feature of the Antarctic species is the presence of two male genital openings (gonopores), unlike most leeches, which have only one male gonopore.

It turned out that the new leech belongs to a group called "platibdellins." They are found in the Arctic and adjacent waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It's like finding a polar bear in Antarctica!

How could such an extraordinary geographical distribution, which biogeographers call bipolar, have arisen? How did a member of the boreal-Arctic group of species end up in Antarctica?

We hypothesized that the ancestor of the new species crossed the tropical waters and ended up in Antarctica. However, in this case, the cold-loving species had to stay for some time in the warm tropical waters and then transition to life in the cold seas of Antarctica. Another explanation could be the temporary cooling of the tropics during global climate changes in the past. Which of these two alternative explanations is correct?

We used modern methods of phylogenetic analysis of DNA sequences, which allowed us to trace the evolutionary paths of the leeches, reconstructed by the program in the form of a phylogenetic tree. Out of millions of possible trees, the algorithm chose the tree with the highest likelihood.

Then we applied Bayesian analysis, which allowed us to reconstruct the geographical distribution of the ancestors of the species we studied. This analysis demonstrated a high probability of our hypothesis that the ancestors of the new species lived in the cold northern waters of the World Ocean and then crossed the tropics to reach Antarctica.

We managed to determine when this event occurred using the molecular dating method. The molecular clock hypothesis was used. Molecular evolution, i.e., the accumulation of mutations in DNA molecules, occurs at approximately the same rate over a long time in different groups of organisms that we studied. But for this, we needed to calibrate our molecular clock using another evolutionary event, if the time when it occurred is known to us.

This calibration event was the emergence of two species of fish leeches of the genus Notostomum as a result of the closure of the Bering Strait 3 million years ago. The landmass divided the range of the ancestral species, leading to the formation of two modern species that now live in the Arctic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean.

Now we had all the necessary information to date the event we were interested in — the crossing of the tropics by the ancestor of our new species. The molecular clock showed that the new species separated from its northern relatives about 1.76 million years ago during the Pleistocene, when the Earth's surface underwent significant cooling. It was during this epoch that the cold-loving ancestor of the Antarctic leech could cross the tropics!

Our phylogenetic analysis and reconstruction of ancestral ranges showed that fish leeches originated in the seas around Antarctica, then spread throughout the World Ocean, reached the Arctic, and penetrated the freshwater bodies of the Northern Hemisphere. However, later the ancestor of our species returned from the north to the homeland of the ancestors of the entire family of fish leeches in Antarctica! Such a convoluted evolutionary history of this species!

We assigned the new species to a new genus, which we named Austroplatybdellina, which translates from Latin as "southern platibdellina," because this Antarctic leech belongs to the predominantly northern group of platibdellins.

The evolutionary history of the new species reminded us of the parable of the prodigal son, who left his father and wandered in distant lands, just like the platibdellin leeches in the northern seas. Eventually, one of them returned to its southern homeland. In Latin, "prodigal" is "prodiga." Thus, the full official name of the new species we described is Austroplatybdellina prodiga.

The main lesson we can take from this story is that climatic changes have significantly influenced the geographical distribution of organisms. Cooling events have occurred repeatedly throughout geological history. We should take this into account and remember the possibility of not only global warming but also global cooling, which can lead to significant changes in living conditions on Earth.

In the bright photos provided by the scientists from their archives, you can see the backstage of science: from the search for truth on the icy continent to meticulous analyses in laboratories.

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).png)